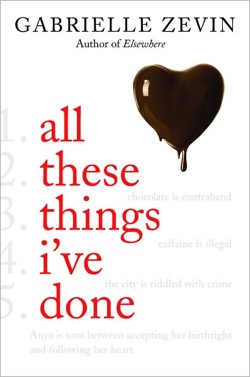

In a not-too-distant future (the year 2083), New York City is crumbling under the weight of corruption. Supplies like water, cloth, and paper are being strictly rationed and chocolate and caffeine have been outlawed as dangerous substances. After witnessing the death of her father, the infamous crime boss and chocolate lord Leonyd Balanchine, sixteen-year-old Anya tries to stay out of the public eye and as far from her family’s chocolate empire as possible. Anya has enough to handle; she is responsible for her a precocious younger sister, an older brother with a traumatic brain injury and her dying grandmother, on top of keeping her studies up at the posh Catholic school where she is mostly ostracized for her unsavory family ties. Falling for a genuinely nice boy (who happens to be the new assistant district attorney’s son) was never in the plan. Caught up in the tides of a mafia upheaval, will Win Delacroix be her only port in a storm, or does their relationship spell her doom?

All These Things I’ve Done could have been just a Romeo-and-Juliet-type love story with a slightly dystopian flavor, but Anya’s conflicted family history and her relatable struggle with modern teenage trials (first love, high-school betrayal, yearning to go to college and escape her identity as a Balanchine) make her an easily accessible heroine with substantial dreams outside of her love affair. While this particular novel isn’t without issues, I can see why Gabrielle Zevin is a nationally bestselling author.

No spoilers.

Anya is an original and complex heroine, which makes up for minor annoyances in her character (such as her slightly pedantic references to her “Daddy” and his maxims), and even her less admirable actions, such as lashing out at a loyal friend, are understandable. She has been saddled with adolescent hormones and adult responsibilities, and she is desperately trying to keep afloat with the added complication of mobster woes. While she is occasionally selfish, and can be thoughtlessly cruel, you can tell how trapped she feels, see how often she sacrifices herself for her loved ones, and you can watch as she grows to be a stronger character throughout the book. I don’t usually like reading from a first-person point of view, but Anya’s practical, confessional, subconsciously wistful tone won me over. (Though I would have preferred a bit less frequent breaking of the fourth wall, since a few of the instances were awkwardly formal, and highlighted gaps in the narrative rather than helping to smoothly change scenes.)

While Anya’s emotional arc was engaging, the plot’s progression was hampered by an overall lack of consistency in pacing and worldbuilding. Brief scenes of intense conflict or action are followed by lengthy passages of introspection and relative teenaged normalcy, such as trying out for the school play. Certain scenes seem to be included just to tie up loose ends or hint at plots for future books in the series, while other potentially interesting plot lines are left with gaping holes. Zevin introduces some intriguing images, like the Balanchine stronghold in a drained Upper West Side pool, or a nightclub called Little Egypt that sprung up in the abandoned Egyptian wing of what used to be the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Yet I often found myself wishing for a more fleshed-out world; I don’t feel comfortable calling this a true dystopian novel, since the reasons for the decline of the city (maybe the country?) were never adequately explained. Aside from a classroom comparison to 1920s prohibition, the decision to outlaw chocolate seemed arbitrary, and my unanswered questions were a distraction from the narrative. (For instance, why water was rationed but electricity seemed like a fairly endless resource?)

Similarly, Zevin has a large cast of interesting characters, but they crop up at unexpected intervals, seemingly introduced early just to set up for future plot lines (Anya’s childhood crush and Japanese chocolate don Yuji Ono, for instance) or are given less plausible motivations for inconsistent actions (Scarlet, I’m looking at you). I want to applaud the author for her inclusion of older brother Leo; she presents an adeptly handled portrayal of life with a disabled sibling, complete with Anya’s adolescent combination of embarrassment, guilt, and fiercely loyal love for her brother. While I could believe that Leo might prove more capable when given the chance to assume some responsibility, I was frustrated at how quickly he seemed to be regaining mental acuity and sloughing off much of what defines his particular level of disability.

Anya’s relationship with Win, the nice boy from the other side of the tracks, is much more plausible, and for the most part, beautifully portrayed. Perhaps some readers won’t like the rush of their blossoming union, but many first loves do happen like that, and Anya displays a refreshing dash of practicality when approaching romance. This is a pleasing contrast to her sensitive young swain, who declares after a kiss that their love is too strong to crumble in the face of his powerful father’s disapproval. Rather than get swept up in the rush, Anya replies that she doesn’t love him yet (though his confident prediction quickly bears fruit). With this star-crossed couple, Zevin showcases her writer-ly prowess, teasing readers alternately with breathless bouts of fumbling physicality and quiet fade-to-black moments of casual sweetness:

The truth is, there were most definitely things that fell through the subway grates, but, at the time, I wasn’t paying attention. Even when I consider all that was to happen in the months that followed, I would not take back those dumb and happy, sweet and foggy, endless, numbered days.

Correction: once, I thought about that tattoo on my ankle. We were in my bedroom, and Win’s lips were on it. He said it was “kind of cute,” then sang me a song about a tattooed lady.

Their relationship was wonderfully authentic, and stronger for Anya’s initial thoughtful reticence and her continuing moral quandary between holding fast to her Catholic beliefs and giving into temptation (though at times her religious moralizing fell flat). Win is almost too good to be true, but is rescued from blandness by his thoughtful clarity and wry sincerity. For instance, after convincing the apprehensive Anya to share some of her contraband dark chocolate, he references the palette of the illegal substance when pitching woo.

“Do you ever wonder if the only reason you like me is because it irritates your father?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “No, you’re the only one who wonders that. I like you because you are brave and far too substantial to ever be called sweet.”

As I mentioned earlier in this review, there were moments when I felt like this book was just setting up for the next in the series. The ending, timed to fall just as summer began (almost as if it were a TV series) was both exasperatingly vague and maddeningly abrupt. Even so, the last chapter was powerfully intriguing, and despite the flaws I found in this book, I am enthusiastically looking forward to the continuing adventures of Anya Balanchine.

Miriam Weinberg is an editorial assistant at Tor. She follows the holy trinity of B’s (Books, Bacon, Bananagrams), though she also likes other letters.